A Chat With: Louise Kennedy

Our wonderful editorial partners, nb Magazine, sat down with the wonderful Louise Kennedy to discuss her debut novel, Trespasses, which is shortlisted for the 2023 Nota Bene Prize. Their editor, Madeleine, chatted with Louise about contested identity and voice as someone navigating Irish political and religious lines, growing up during the Troubles.

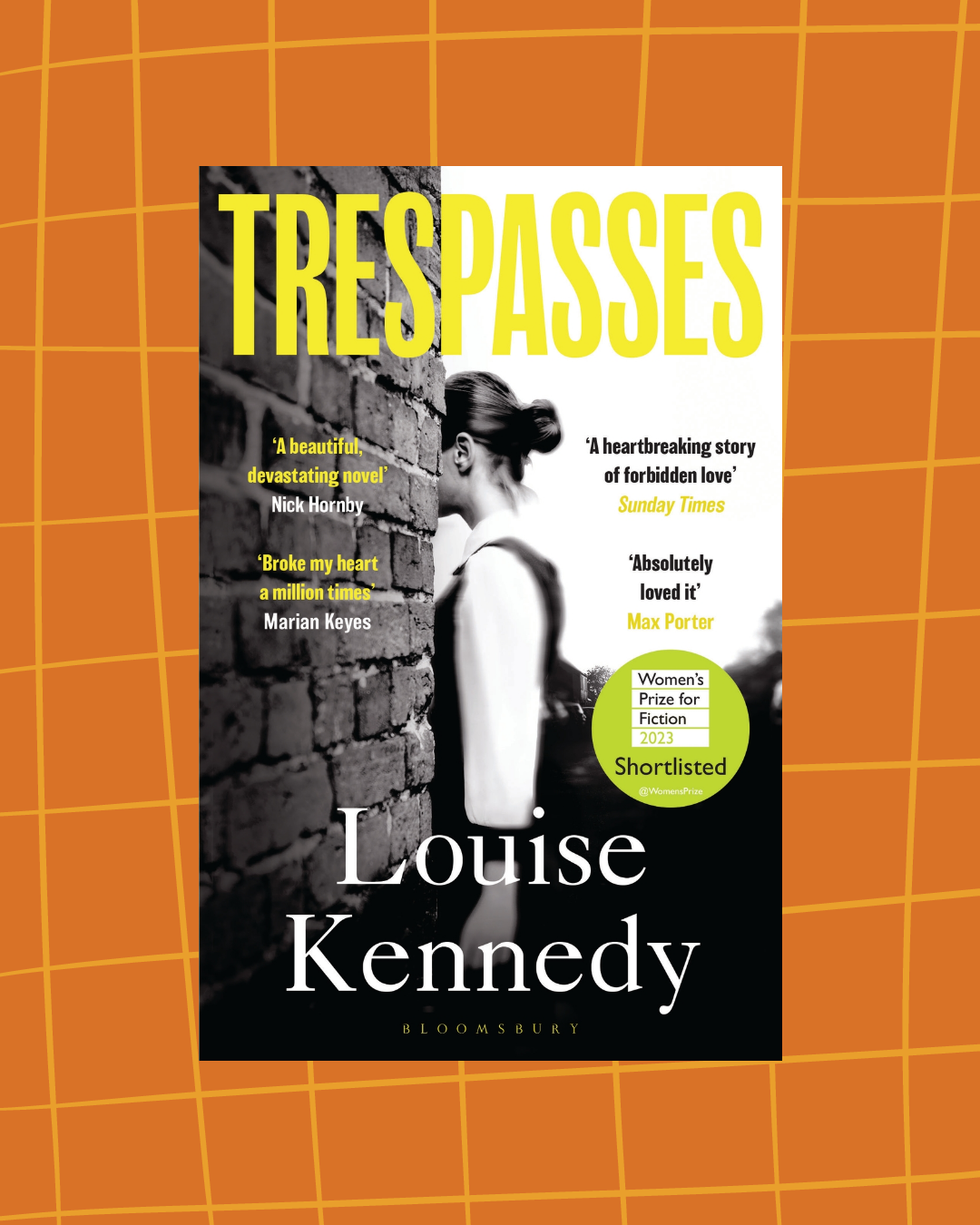

Set in 1970s Belfast, Trespasses is a quietly heart-breaking and captivating love story written by Louise Kennedy, who swapped the chef’s whites she had worn for three decades for writing, when she published a collection of short stories entitled The End of the World is a Cul de Sac. Despite coming to fiction later in her life, Kennedy’s beautiful and attentive debut novel has confirmed her place in the company of the swathe of gifted Irish authors writing today.

First of all, would you be able to tell us a little bit about how your debut novel came about and what was your writing process like? Did it differ from writing short stories?

Lots of things were different about the process and I suppose the reason for writing the novel possibly came from a different impulse that I had from writing the stories. With the stories, I started to write when I was asked to join a writing group, which meant that straight away I was given deadlines and every week I went into a room where people were presenting writing that was being workshopped. And it’s no exaggeration to say that I hadn’t written – I literally hadn’t written a word since school, and nothing we did in school was creative writing, so I really hadn’t written anything. So, I suppose the reason I wrote short stories was simply because that was the unit of fiction that was required of the writing group I joined, and then it was also what was required when I did an MA in Creative Writing.

And then, after that, I decided to do a PhD, which I thought was a really great idea, but I think it was my version of a midlife crisis! I don't even have an undergrad English degree and I had to write a few chapters of a book to PHD English standard and I think it gave me a nervous breakdown. But anyway, towards the end of the MA year, I wrote a short story called Hunter Gatherers, and I think with that I felt I’d hit on something that was probably a bit more sophisticated – I think maybe I’d found a voice and tone that I liked and felt comfortable with. Also, I think that Hunter Gatherers has a very strong sense of place, so with the stories I wrote for the PhD, I just tried to keep those things in mind, and it definitely felt like something was beginning to happen with the stories – they were starting to get a lot more complex.

And then I’d written one of the last stories that I wrote for the collection – it’s set in the North and it opens in a bar and it's about obsession and a teenager or young woman going through the collateral damage of the troubles – and, although I didn't realise it, I think I was probably fleshing out my ideas for the novel.

Also, I suppose I also started to write the novel because it was a kind of procrastination from writing up the creative part of the PhD… I couldn't be completely idle, but I thought that if I at least wrote something then it means that I’m not a lazy b******, so I started to work on an idea. And then, in March 2019, I got a cancer diagnosis and it did a few things to me. I didn't really let myself dwell too much on the big picture because you can’t really go through life like that, but I did think that, if I was going to write a novel, I couldn't just presume that I had decades and decades to do it, so I just thought I should just try and get a draft down while I could. So after 11 weeks, I had around 62,000 words, which sounds impressive, but looking back, I was very lucky that I actually had a project that I could throw myself into. I think that helped me in lots of ways. By June 2019, I had something that resembled a novel – in length at least. It wasn’t very good and I left myself a hell of a lot to clean up for the second draft.

And how does it feel now that the book is out there and published? Is it still true that you feel uneasy with all the praise you’re receiving, or do you feel a sense of accomplishment?

This kind of fascinates me. I have done some teaching and I’m always just baffled when people come in with a piece of work that they're really, really happy with. I totally get that a person can be happy with having made something new, but how can they be happy with the writing? I'm really glad for them, but no, I’m never happy at all and I think that’s as it should be.

Do you think that’s because we all tend to think that everything we create can always be better?

Yes, I do, I think there’s that. Also, I haven’t been at this long enough that I can call myself an artist or a writer or something, and although I'm really delighted for anybody else who is comfortable with it all, I think because I did my last shift in the kitchen about three years ago, I just can't be doing with that. I just feel like I’m a chef with notions. I think most of my neighbours didn’t even know I was writing until the Sunday Times Audible Awards when they opened the Sunday supplements and saw my big face there and thought, what?

Trespasses is set in a town in Northern Ireland where there were very few Catholics, which mirrors the surroundings you grew up in. Because of the fact that you are writing about a time and place that you know very well, do you find that you are identified by your nationality? How do you feel about being labelled a ‘Northern Irish writer’.

That's really interesting. I come from probably one of the places in Europe where identity is most contested and it’s really interesting to me. I left when I was 12 and we went to the South because, I suppose, my parents had had enough of the north by the end of the 70s for a lot of reasons that are well documented – you know, there were bombs and things. I didn’t want to move but they sold us the idea as if we were going to the promised land where we wouldn’t have to run around pretending we weren’t Catholics. But really, it was a s******* theocracy in the late 70s and, you know, the health service was pretty poor, people were very narrow-minded, and I didn't really find it a fabulous improvement in lots of ways. I guess it was a relief that people weren’t getting killed on a daily basis, but I didn’t find it so great.

I found it hard to settle and every time I opened my mouth I was teased, it was just really exhausting being different. So I got rid of my accent pretty quickly and I'm not very proud of that, but in a weird way, I think it's why I wrote the book that I did. When I speak, people from the north don't think I’m a northerner and people in the south don't think I’m a northerner. For example, somebody from Belfast follows me on Twitter and has read my writing and she messaged me to say she nearly crashed her car when she heard me on the radio because my accent was really Southern and she couldn't believe I would speak like that when every word I write comes across as very northern.

I had really felt that I had lost my northern identity or my northern voice, but when I write I get it back, and I think that's why it was very restorative for me to write, and that's why I feel right in myself – it's really strange.

I’m also really interested in the idea of a northern voice – I read that you describe this voice as “grim humour and anxiety, a kind of cheery nihilism [and] an unease in relationship with place.”

Yes, I think so! In the early days, I made the mistake of going online to see what people have said and, I know that Trespasses isn’t a very cheery story, but some people had read it and had absolutely not seen any humour in it and that baffled me. I think my relationship with language is probably a bit different because I grew up in a place where the way that we spoke was peppered with words of Ulster Scots. When we moved to the South those words were kind of redundant, but they’re all still there in my vocabulary. I’m probably working off a few different lexicons.

But anyway, back to identity – my family always identified as Irish, we never identified as British, but we couldn’t be public about that in the place where we lived, so we just kept our heads down. And then, I suppose because we lived in the South for so much of my life, the Irish thing isn't in dispute for me at all. But, with regards to calling the north Northern Ireland with a capital ‘N’ – I don't really like that. To elaborate on that is just going to end up in conversations that I never really intended to have because it suggests a political position, so I guess I just have to keep reminding myself in conversations about identity that all I wrote is a love story that happens in the 1970s! But when other northern writers claim me as one of them, I'm so happy I could cry.

Could you tell me a little bit more about the process of building the characters – they were so real and layered and have really stayed with me. How did you approach characterisation?

I suppose, with Cushla herself, it wasn't so difficult for me to visualise her because she was probably a little younger than my mother was in those days – my mother had me when she was 19. And also, when I was a teenager, my father's younger sister lived with us for a while, so there were elements of her in there. I mean, I knew that Cushla was going to fall for somebody older and I guess I knew what the basic premise was going to be. I also knew the details like the type of clothes they wore, what their rooms looked like, what car they would drive, what they smell like and what they like to eat – all of those details are much more vivid to me than their inner thoughts, so I tend to rely on showing how people are in their own bodies and how they react to what’s around them. So maybe developing a character, for me, is about throwing s*** at them to see how they react.

Where did the title of the book come from?

Oh, it was going to be called When I Move to the Sky which is the name of the song that Michael sings, but my editor Alexis was never particularly happy with it and a lot of people thought it was maybe a bit whimsical and it wasn't really sticking, so we tried to come up with something shorter and Trespasses came to me. For me, it works on a number of levels. It’s a word that children learn when they learn the Lord's prayer, but it's a really strange word and it's not one that you hear very often – except for in that prayer –so it does sound a bit biblical. I guess it also suggests that lines are being crossed all over the place – religious, class, moral, and also literally, in that Cushla is going to parts of Belfast that she wouldn't normally go to.

I was so interested that you were a chef before you started writing and I wanted to ask you whether you feel there are any parallels between the practical work of being a chef and an author?

I do think certain parts of the process are really similar. When you work as a chef, you're working when everybody else's having fun, the working conditions are pretty ****, and a lot of it isn’t about the sexy, high-adrenaline cooking. A lot of it is just about peeling and chopping and getting ready and I think that maybe that does have some parallels with any creative practice. I think certainly, turning up when you don’t feel like it is the best lesson of all. You know, it's practice. It's not the case that people have amazing ideas and then they sit down and write it all down. You have to turn up every day.

What are you reading now?

There's a book that's going to be published in July by a writer called Jane Campbell – she's 80 now and her debut is called Cat Brushing and it is amazing. The other thing I'm reading at the moment is called The Sun is Open, and it’s by a poet in Belfast called Gail Mcconnell and it's just wonderful.